Date:23 October 2025

Seções de conteúdo

- ● The eight characteristics of life

- ● CHARACTERISTIC 1 – Energy: living systems ride gradients, far from equilibrium

- ● CHARACTERISTIC 2 – Matter: where chemistry and physics meet biology

- ● CHARACTERISTIC 3 – Organisation and boundaries: the living is bounded and homeostatic

- ● CHARACTERISTIC 4 – Information: genomes that store, process and express meaning

- ● CHARACTERISTIC 5 – Bioelectromagnetism: energy fields for informational control

- ● CHARACTERISTIC 6 – Reproduction: continuity of organised complexity

- ● CHARACTERISTIC 7 – Evolution: heritable variation enables open-ended change

- ● CHARACTERISTIC 8 – Life purpose: teleonomy and beyond

- ● Note on the Dalgleish line

Professor Angus Dalgleish and I were both presenting at a Klinghart Institute conference in Turin, Italy, last month. In my presentation, I tackled the question of ‘what is life?’. My justification for this focus was three-fold: firstly, there appears to be little consensus on answers to this question even among scientists; secondly, it seems important we know what life—and human life in particular— is if we are to help enhance our health or quality of life by way of this discipline we call ‘medicine’, and; lastly, and perhaps most importantly, we owe it to future generations to understand what life is—especially what it is to be human—at this point in history when it is our generation that sits at the cusp of the bifurcation where we can choose to remain as organic humans or take the transhuman route in which we start integrating human—or artificial intelligence made, synthetic elements to our bodies, minds and potentially even our consciousness.

After my delivery, the good professor handed me a piece of paper, with his definition of life in just one sentence. I was blown out, because he encapsulated so much in a few words, when I’d taken 30 minutes to try to explain it, albeit with additional elements included. As Nietzsche once said, “It is my ambition to say in ten sentences what others say in a whole book.” At that moment I felt Professor Dalgleish was Nietzsche, and I was the “others.”

Encapsulated here that one sentence of wisdom from the co-discoverer of the CD4 receptor so crucial in HIV infections:

“Life is a non-linear adaptive mechanism of using up excess energy in the local universe.”

– Prof Angus Dalgleish

This really plays on the thermodynamic element of life. Life does indeed run far from equilibrium and survives by dissipating energy gradients. But I come at this as a biologist and ecologist with a passion for biochemistry, biophysics, metaphysics and all things multi- and trans-disciplinary. The Dalgleish definition, while beautifully concise, left out features that most biologists would treat as non-negotiable—heredity, boundaries, information, and the capacity to evolve.

Could things that were clearly not living be encompassed by his definition? I thought so. What about hurricanes and fire? I think they do fit. In recognising the limitations of the Dalgleish definition, I felt driven to explore this further, so please read on if you’d like to come on this journey with me.

The eight characteristics of life

I propose there are eight interlocking characteristics of life that can be considered under the headings of energy, matter, organisation, information, reproduction, evolution, and purpose. As I consider each, I will offer at least one seminal piece of published scientific work as a hyperlink that I hope helps to cement the validity of the specific characteristic of life in your mind. I will end this piece by proposing a new, Nietzsche-inspired, shortish definition of life that preserves Professor Dalgleish’s thermodynamic insight while attempting to add what I feel was missing.

CHARACTERISTIC 1 – Energy: living systems ride gradients, far from equilibrium

Let’s start where Dalgleish did. Life is thermodynamically open: it persists by channelling energy and matter through itself and exporting entropy. The field of disequilibrium physics has really helped to sharpen this view of life. Look here at Prigogine’s “dissipative structures,” Albert Goldbeter’s work on biological rhythms, or Jeremy England’s “dissipative adaptation,” showing how driven systems can self-organise to better absorb and dissipate work. This whole area is wonderfully reviewed by Goldbeter in his paper published in 2018 in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

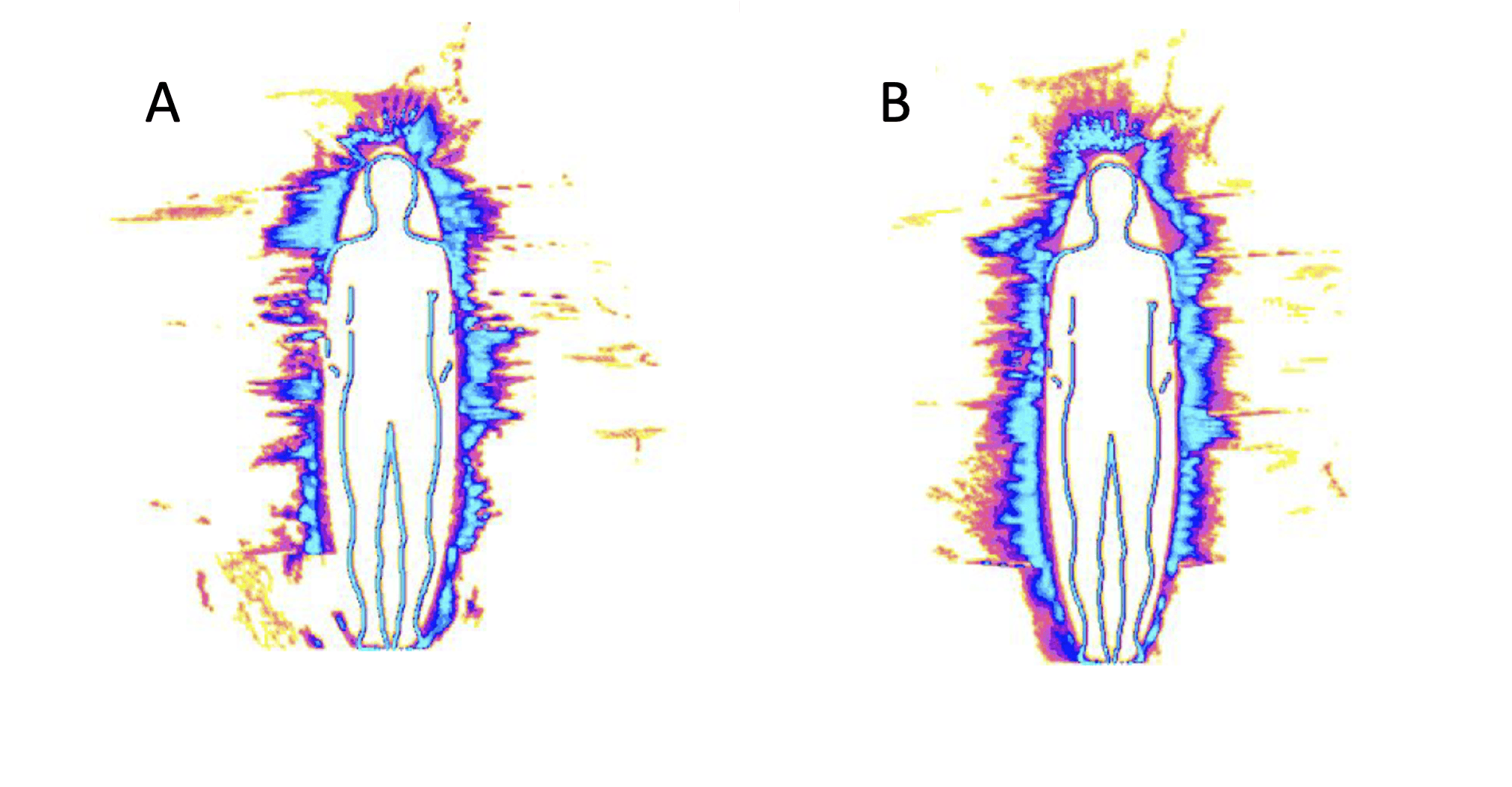

Let’s also be broadly sighted when we look at energy in relation to life. There’s the biochemical energy of living organisms that exists as matter, such as the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) that is the biochemical energy of animals as produced by mitochondria. Then there’s the bioelectricity that runs our nerves. And the biophotonic output that makes us truly beings of light (read more about this in Characteristic 5). And, of course, the electromagnetic energy issued by our hearts (as measured by ECG), brains (measured by EEG), and bodies (MRI, kirlian photography, gas discharge visualisation, etc.). The term biofield attempts to sum up the overall bioelectrical, electromagnetic and subtle energy flows—the life force if you will—of our bodies. These energies have long been recognised the world over. There’s the qi in Chinese medicine, prana in Ayurveda, ki in Japan, the kawsay of the Quechua in the Andes, the ka of Ancient Egypt, the igbo chi of West Africa, the kurunpa of the Central Desert Aborigines…the list goes on. Were these peoples all just ignorant or wacky? Hardly. They knew things that modern biophysics is only just starting to explain. They recognised the potential for non-local, non-linear effects that quantum physics and entanglement theory only started trying to explain a few decades ago.

This dynamic, energetic lens explains why Dalgleish’s line resonates. But energy dissipation alone isn’t sufficient. Many non-living systems dissipate energy; among the things that makes life vida is how that flow sustains organised, bounded, information-rich processes across time.

Figura 3. Composite aura for normal healthy female (50) before (A) and after (B) administering therapeutic touch therapy. Image from part of a range of studies undertaken by Dr Konstantin Korotkov as summarised in a book chapter by Beverley Rubik PhD of the Institute for Frontier Science (Oakland, California).

CHARACTERISTIC 2 – Matter: where chemistry and physics meet biology

Simply put, the fundamental physical matrix that appears to make life on Earth possible relates especially to carbon chemistry in water, scaffolding membranes, proteins and nucleic acids. All these things are made up of molecules that are in turn comprised of atoms that can all be found on the Periodic Table. Origin-of-life research that looks at how prebiotic life could develop into early, cellular life consistently comes back to two basic premises: you need compartments (proto-membranes) and informational polymers (RNA-like molecules) to make life happen. Jack Szostak’s group at Massachusetts General Hospital, for example, explains how simple fatty-acid vesicles grow, divide and exchange nutrients. That may well tell us something about the how—but what tends to be missing from such accounts is the ‘why’ (keep reading).

CHARACTERISTIC 3 – Organisation and boundaries: the living is bounded and homeostatic

Life isn’t just a bunch of informational molecules and cells; it entails an extreme level of organisation of atoms and molecules that exist elsewhere on the planet (and sometimes elsewhere in the solar system or universe) that are linked in, and network in, highly specific ways that allow self-regulation. Importantly, these systems are also clearly separated from the external world. Cells and organisms are thus bounded systems (membranes, tissues) that maintain internal conditions—homeostasis—while exchanging energy and matter with the environment. The term autopoiesis is used describe this self-producing, self-maintaining organisation that’s intrinsic to life. Even detractors (e.g., here and here) agree that the boundary-making, networked metabolism notion captures something fundamental to living systems.

CHARACTERISTIC 4 – Information: genomes that store, process and express meaning

Biology is awash with information. Most chemicals like hormones, peptides and cytokines are ‘infochemicals’ that communicate with other cells and tissues. The more we learn about this, the more we recognise these communications are not solely molecular or chemical. They are also electromagnetic. Take for example the way in which the 4 nitrogenous bases of the DNA alphabet always pair up as A and T, or C and G. It’s a kind of spooky attraction at a distance that suggests the interplay of quantum effects (entanglement theory) in biology.

Take another example: food. It’s so much more than an energy carrier (calories). Food is information—that’s why 100 calories of ice cream does something very different to our bodies compared with 100 calories of broccoli. There is a mass of functional instructions that is expressed from our genes that are selected, deselected or preserved by the evolutionary process of natural selection. As NIH distinguished, NCBI-based, Russian-American biomedical researcher Eugene Koonin put it in his 2016 review, biological information involves meaning: encoding functions with varying degrees of conservation. Recent work on genotype–phenotype mapping shows how sequence changes percolate through folding, networks and development to yield form and function. Incidentally, and relevant to any consideration of transhumanism (read on), they also reveal insights that are central to developing human-designed artificial systems and synthetic biological systems.

Information in living systems is processed in real time: transcriptional control, signalling pathways, and (see CHARACTERISTIC 5 below) bioelectric and electromagnetic dynamics help tissues coordinate growth and repair.

CHARACTERISTIC 5 – Bioelectromagnetism: energy fields for informational control

Generally accepted science tells us that life is at the very least a physico-chemical–electromagnetic phenomenon. Across the tree of life, ionic currents and electric fields pattern tissues; membrane potentials carry instructions for growth, regeneration and form. Orthopaedic surgeon Robert O Becker brought the significance of bioelectrical forces to the fore when he described, in his 1998 book, The Body Electric, how broken surfaces of bones are bioelectrically drawn to each other to assist functional bone healing, and how damaged limbs, organs and spinal cords could—under certain conditions—regenerate, like a salamander’s tail. A 2019 review by American developmental and synthetic biologist Michael Levin and colleague Kelly McLaughlin from Tufts explain the “interplay between molecular-genetic inputs and important biophysical cues that direct the creation of tissues and organs” and detail how bioelectric circuits store non-genetic patterning information and can be manipulated to trigger organ-level changes.

>>> Frequency Medicine (Part 1) – unearthing the mysteries of life

But that’s not all. Fritz-Albert Popp confirmed, in the 1970s, earlier work that showed that all organisms emit ultra-weak photons (biofótons). These emissions are measurable and correlate with physiological state. Cancer patients emit less biophotonic energy than healthy people. Yes, we are truly beings of light—as are all known living organisms. When we die, the lights go out—literally.

We should remind ourselves that clinical definitions of death are tied not to the loss of any biochemical activity but rather to the permanent loss of characteristic electro-physiological activity, notably in the brain stem.

CHARACTERISTIC 6 – Reproduction: continuity of organised complexity

Life persists by reproduction—that varies from simple cell division through to sexual reproduction—so that its organisational blueprint is perpetuated, incrementally adapting subsequent generations to changing environments through processes such as natural selection and epigenetics. NASA’s widely used working definition—“a self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution”—keeps this front and centre. The Astrobiology department at NASA provides interesting insights when assessing the criteria required to detect life, stating:

“Living systems that have emerged on Earth have done so by a process of random variation in the structure of inherited biomolecules, on which was superimposed natural selection to achieve fitness. These are the central elements of the Darwinian paradigm”.

Sexual reproduction, in particular, it seems, exists for the purpose of allowing open-ended change to dynamic environments, taking us straight to Characteristic 7. Imagine if we all found it a chore!

CHARACTERISTIC 7 – Evolution: heritable variation enables open-ended change

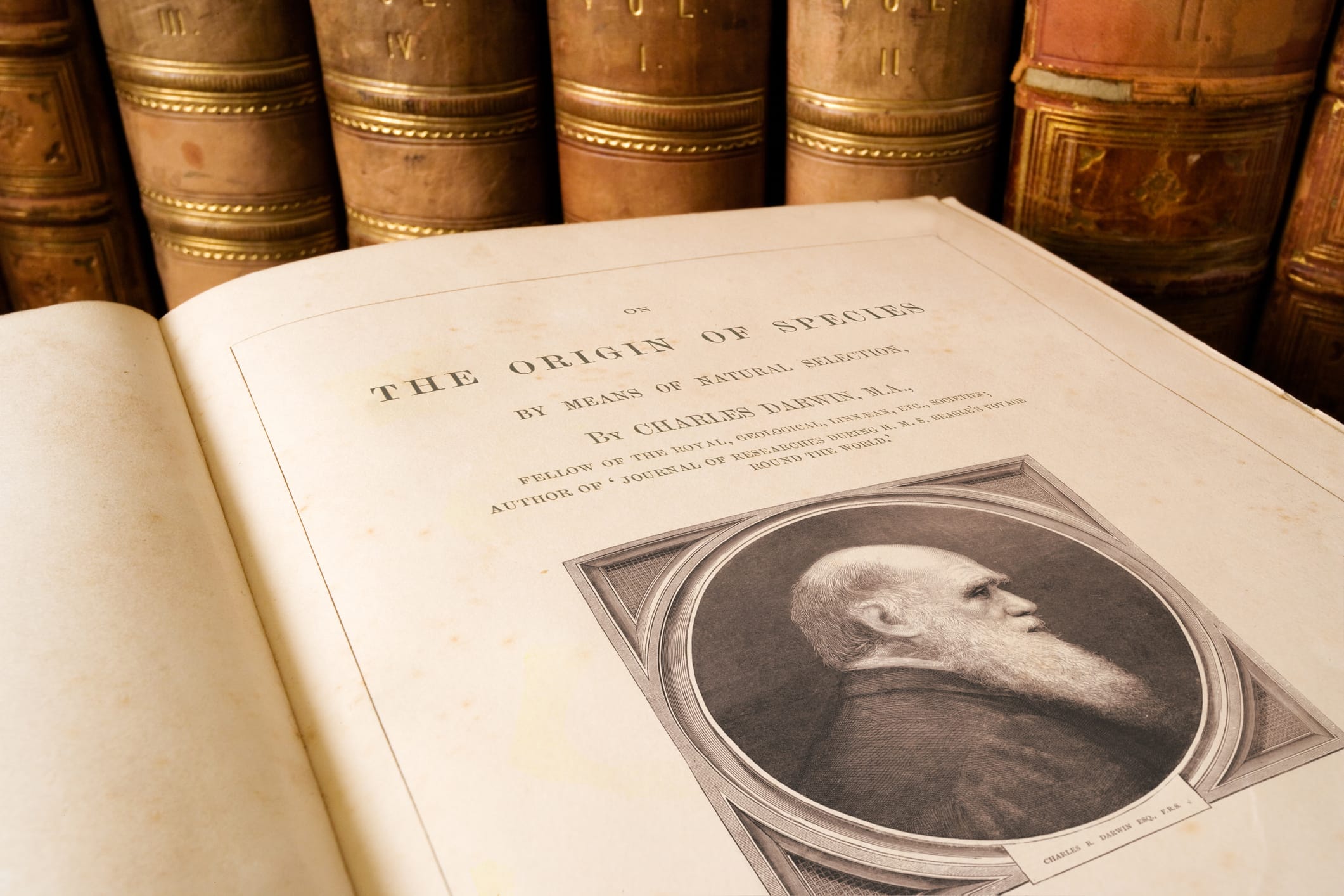

A defining signature of life is replication with heritable variation under selection. That’s why fires and hurricanes, though they dissipate energy and can change shape, aren’t alive: they don’t inherit! Evolutionary theory, coupled to genotype–phenotype work, shows how information becomes reliable enough to preserve function and yet plastic enough for innovation.

As evolutionary research extends beyond the somewhat limited Darwinian paradigm, we are learning a lot more about the role played by viruses. Those nucleic acid containing pseudo-living entities that are distributed in pretty much every environment on our life-abundant planet, appear to play a vital and major role in evolution by acting as critical vectors of gene transfer between organisms.

CHARACTERISTIC 8 – Life purpose: teleonomy and beyond

Organisms behave as if they have purposes. They seek particular foods available in their niches, move in ways fitted to their habitats, repair damage, and preserve viability long enough to reproduce and care for offspring. Classical thinkers wrestled with this “purpose” long before modern biology: Plato framed ends as extrinsic (tied to ideal forms), while Aristotle argued for intrinsic “final causes.” Contemporary biologists avoid metaphysical claims and instead use teleonomy—the idea that apparent purposefulness in living systems arises from evolved structures and control processes. In short: goal-directed behaviour without invoking external design (read: the metaphysical, the mystic, God, spirituality, etc.).

Biologists, like so many other specialists in their respective fields, like to limit their view to ideas and concepts that are familiar to them. Therefore anything mystical, metaphysical or spiritual is removed from the equation. It may also be dismissed as too anthropocentric. But just because we don’t understand something, it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. This line of thought takes us directly to the interface of science with spirituality, an area that has fascinated philosophers for centuries. As we delve, feel and connect at deeper levels we sometimes get to recognise the sanctity of life. It’s not something we can prove or disprove, but it is something we feel so profoundly that it can feel more true, even to a scientist, than the most carefully controlled, high quality experiment.

I’ve mapped out above two contrasting views of the purpose of life, but it’s really more of a stack with even more than these two contrasting perspectives on purpose in life, with different levels speaking different languages:

- Biological purpose (teleonomy): survival, growth, repair, reproduction—implemented by homeostatic and developmental control networks.

- Organism-level agency: learning, anticipating, and selecting among options to reduce uncertainty and maintain integrity over time.

- Ecological reciprocity: behaviours that sustain the niches including those that sustain us—mutualisms, trophic feedbacks, and how well different species are adapted to specific niches or habitats.

- Human meaning: altruism, conscious projects, higher values, and callings—this kind of purpose or meaning is experienced subjectively but is shaped by biology, environment, culture and sometimes also by spirituality.

Perhaps it’s not pure chance that nature can be both so purposeful, so beautiful and can deliver so much healing. In fact, I will propose that one of the major reasons we are facing an increasing and seemingly unstoppable burden of chronic disease is because we, as a species, are increasingly disconnected from nature.

We are more and more disconnected from the microbes that train our immunity, the light cycles that tune our clocks, the chemical and electromagnetic cues our bodies evolved to expect, and the living places that help us regulate stress. Diet and targeted exposures to the right kinds of nutrients and natural products can help greatly, but so does the simple act of being in nature—seeing, touching, breathing, and attending to living systems. A growing body of research links regular time in green and blue spaces to lower allostatic load, improved mood and cognition, and markers of immune and cardiometabolic resilience. However you interpret it—biophilia, environmental enrichment, or spiritual reverence—recognising and reciprocating with nature appears to be not just pleasant but salutogenic.

This reciprocity between humans and nature may be fundamental to us being happy and healthy, two things we are most definitely struggling to achieve. Our anthropocentricity means that human cultures have long valued looking after their elderly parents given they were responsible for their lives. But too many don’t apportion this same reciprocity to the natural environments from which the material parts of our being originate.

I did say at the outset my intention was to be brief à la Nietzsche, so I must draw this essay on life to a close.

But I will leave you with something to ponder: let us think very carefully how we transgress the boundaries of life with gene-editing, somatic gene therapies, lab-grown organs, mRNA technology, brain-computer-interfaces, AI augmentation of cognition or memory, implantable devices, precision fermentation, synbio foods, and all the other elements that are associated with the onward creep towards transhumanism.

Let us move forward freely, eyes wide open. Consensually. In the knowledge that we will not all want to take the same road. Respectfully.

Note on the Dalgleish line

I opened with Professor Dalgleish’s scrawled and his insightful definition of life. With the insights I’ve shared with you, each of which have, I believe, a plausible scientific basis, let me give you a less concise, but nevertheless, more encompassing definition of life:

“Life is a bounded, self-organising, far-from-equilibrium physico-chemical–electromagnetic system that maintains homeostasis by transducing energy and matter; encodes and processes information to preserve its organisation; and reproduces with heritable variation, enabling open-ended evolution with purpose.”

___________________________

Please help to circulate this article widely through your networks. Thank you.

>>> Se ainda não está inscrito no boletim informativo semanal da ANH International, inscreva-se gratuitamente agora utilizando o botão SUBSCRIBE na parte superior do o nosso sítio Web - ou melhor ainda - torne-se membro do Pathfinder e junte-se à tribo ANH-Intl para usufruir de benefícios exclusivos dos nossos membros.

>> Não hesite em republicar - basta seguir a nossa Alliance for Natural Health International Diretrizes de republicação

>>> Regresso para a página inicial da ANH International